The promise of LASIK (Laser-Assisted In Situ Keratomileusis) surgery is often framed in absolute terms—a definitive escape from the burdens of glasses and contact lenses. This perspective, however, overlooks the dynamic and biologically continuous process of human vision and ocular aging. LASIK is a highly sophisticated, permanent modification of the corneal shape, designed to correct pre-existing refractive errors like myopia (nearsightedness), hyperopia (farsightedness), and astigmatism. It successfully corrects the structural flaw present at the time of the procedure, granting a remarkable degree of functional vision clarity. Yet, the human eye is a living organ, and its dimensions and function are subject to change throughout a person’s life, influenced by genetics, environment, and, most powerfully, the inevitable onset of presbyopia and other age-related ocular shifts. Therefore, the question of whether LASIK eliminates the need for glasses forever necessitates a nuanced exploration of what the surgery actually fixes, and what biological mechanisms it cannot, and should not, attempt to control.

The Dynamic and Biologically Continuous Process of Human Vision and Ocular Aging

This perspective, however, overlooks the dynamic and biologically continuous process of human vision and ocular aging.

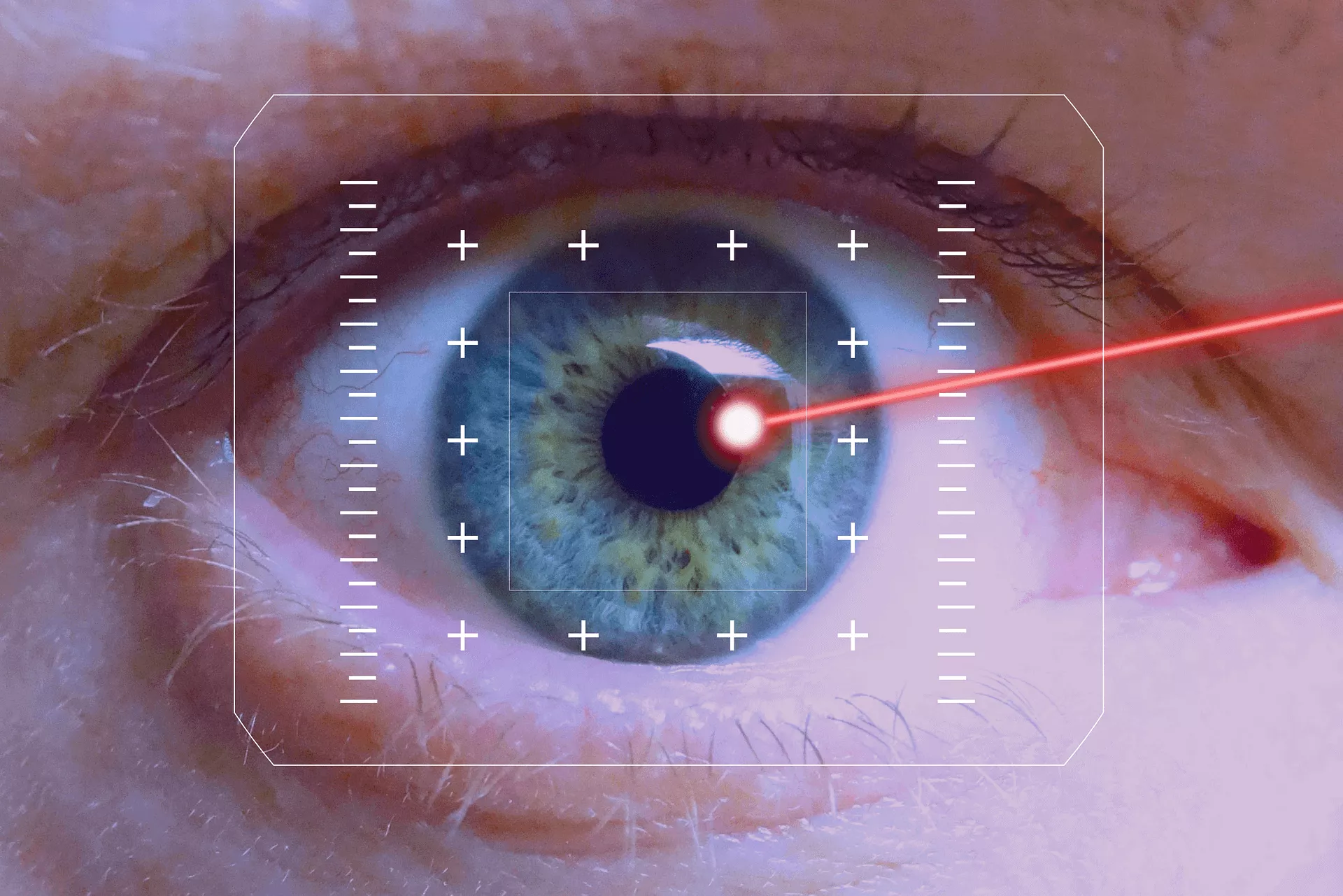

To grasp the longevity of a LASIK result, one must appreciate that the eye’s focus is governed by two main components: the cornea and the lens. The cornea is the eye’s primary, fixed focusing lens, and its shape is what LASIK permanently alters. The crystalline lens, located behind the iris, is the eye’s secondary, adjustable lens; it changes shape via the ciliary muscles to focus on objects at varying distances (accommodation). LASIK’s success is defined by the stability of the corneal correction and, for the vast majority of patients, that correction is highly stable and permanent. The structural change etched into the cornea by the excimer laser does not spontaneously revert. However, the eye’s overall refractive power is constantly mediated by the natural, internal changes occurring within the aging crystalline lens, making the final visual outcome a continuous compromise with biology.

The Stability of the Corneal Correction

LASIK is a highly sophisticated, permanent modification of the corneal shape, designed to correct pre-existing refractive errors.

The fundamental achievement of LASIK is the permanent modification of the corneal shape. The excimer laser ablates, or precisely removes, microscopic layers of tissue from the corneal stroma to reshape the cornea so that light focuses directly onto the retina. Once the corneal flap has healed, this new curvature is structurally permanent; the eye doesn’t “grow back” the tissue in a way that undoes the correction. Studies tracking patients over two decades consistently show that the majority of patients maintain a near-perfect corrected visual acuity. Any minor, subtle regression that may occur in the first few months after surgery is usually minimal and is typically addressed during the initial recovery phase, often attributed to the settling of the corneal bed or minor wound healing responses, but the foundational correction holds firm.

The Inevitable Onset of Presbyopia

The inevitable onset of presbyopia and other age-related ocular shifts.

The single most common reason a successful LASIK patient may need glasses again is the completely separate, age-related condition known as presbyopia—the loss of near-focusing ability. Presbyopia typically begins to manifest in the early to mid-40s and is a universal phenomenon; it affects everyone, regardless of whether they have had LASIK or wore glasses their entire life. It is caused by the natural hardening and reduced flexibility of the crystalline lens, not by a failure of the corneal LASIK correction. When the lens can no longer adequately change shape to focus on close objects (like a smartphone screen or a book), reading glasses become necessary. LASIK surgeons can sometimes preemptively address this with techniques like monovision (correcting one eye for distance and the other for near), but presbyopia itself is a non-refractive aging process the laser cannot prevent.

Unmasking Subtle Post-Operative Refractive Changes

The structural change etched into the cornea by the excimer laser does not spontaneously revert.

While the major refractive error corrected by LASIK is permanent, it is possible for subtle, minor post-operative refractive changes to occur years later. This is often not a “failure” of the LASIK, but rather the unmasking of natural, genetic shifts in the eye’s overall axial length. As the eye subtly changes dimension over the decades, the precise focal point can shift slightly, potentially leading to a minimal return of myopia or hyperopia. This is more common in individuals who had very high degrees of nearsightedness initially, as their eyes may be genetically programmed to continue subtle changes. If this shift is significant enough to interfere with functional vision, a LASIK enhancement (a touch-up procedure) may be an option, provided the corneal tissue remains thick enough to safely permit further laser ablation.

The Role of Cataract Development

The human eye is a living organ, and its dimensions and function are subject to change throughout a person’s life.

The long-term need for glasses or a surgical intervention is also influenced by the eventual development of cataracts. A cataract is the progressive clouding and yellowing of the eye’s natural crystalline lens, which begins, to some degree, in everyone past the age of 60. Cataract formation significantly changes the eye’s refractive power, often inducing a shift towards myopia as the lens becomes denser. Crucially, a cataract must be surgically removed and replaced with an artificial intraocular lens (IOL). At the time of this cataract surgery, the surgeon can select a modern IOL that simultaneously corrects the patient’s existing vision, essentially replacing the original LASIK correction and eliminating the need for glasses or contacts once again, though this is a completely separate procedure from the initial laser vision correction.

Environmental and Health Factors

The final visual outcome a continuous compromise with biology.

Beyond age-related factors, a patient’s overall systemic health and environmental exposures can subtly affect the long-term quality of their LASIK outcome. For example, conditions that compromise the quality of the tear film, such as chronic dry eye, can lead to fluctuations in vision and perceived blurriness that may necessitate the temporary use of reading or low-power glasses to sharpen focus. Furthermore, certain systemic diseases, notably uncontrolled diabetes, can cause temporary but significant shifts in blood sugar levels that, in turn, alter the swelling and shape of the natural lens, temporarily changing the eye’s refractive state. While the LASIK correction remains physically stable, these metabolic or environmental shifts can impact the functional clarity of vision.

Setting Realistic Expectations

Understanding this temporal trajectory—that the surgery resets the aesthetic clock rather than stopping it—is crucial for setting realistic, long-term expectations.

Effective patient counseling involves clearly differentiating between refractive error correction and ocular aging. LASIK provides an incredibly long-lasting and effective solution to the former, but it is powerless against the latter. Understanding this temporal trajectory—that the surgery resets the aesthetic clock rather than stopping it—is crucial for setting realistic, long-term expectations. Patients should be told that if they have the procedure in their twenties, they should expect to need reading glasses in their mid-forties, and potentially a cataract surgery in their sixties or seventies. These future needs are not failures of the laser surgery but are simply the normal, predictable passage of the human lifespan and the life of the human lens.

Monovision: A Compromise with Presbyopia

LASIK surgeons can sometimes preemptively address this with techniques like monovision.

For patients who are approaching the presbyopic age range (mid-30s to early 40s) and are determined to avoid reading glasses for as long as possible, the LASIK surgeon may discuss the option of monovision. Monovision involves deliberately correcting the dominant eye for sharp distance vision and leaving the non-dominant eye slightly under-corrected (or targeting it for slight nearsightedness) to facilitate comfortable near-focusing. While this can successfully delay or eliminate the immediate need for reading glasses, it is a compromise. It relies on the brain’s ability to seamlessly integrate two different visual inputs, which some patients adapt to easily and others find challenging, potentially causing subtle losses in depth perception or twilight vision. Therefore, monovision is often tested first with contact lenses before being permanently set with the laser.

The Lifespan of an Enhancement

If this shift is significant enough to interfere with functional vision, a LASIK enhancement (a touch-up procedure) may be an option.

In cases where a patient experiences a significant, measurable refractive shift years after the initial LASIK, the decision to proceed with a LASIK enhancement—a touch-up procedure—must be carefully considered. The longevity of this enhancement is typically tied to the same stability achieved with the initial surgery, meaning the new correction is also largely permanent. However, the patient must be assessed for adequate residual corneal thickness. Since the enhancement removes additional tissue, the surgeon must confirm that the cornea remains thick enough to maintain structural integrity and prevent a rare, but serious, complication called ectasia. If the residual thickness is insufficient, other, non-laser options (like PRK or the use of phakic IOLs, though rare) must be considered, or the patient must simply wear glasses for the minor correction.